Lidl, Morrison’s And The Self-Tipping Hat

What do a supermarket, one of the world’s biggest blogs and a Victorian entrepreneur have in common?

If you’re trying to sell anything, they should have it in common with you, too.

To work it out, think: what did it mean to be a Victorian entrepreneur?

The thing is, life was hard for the Victorian gent. Officer commissions were no longer available for purchase, meaning the gentleman soldier may have to share the mess with the lower classes. Proper dress insisted on waistcoats even in summer. And a man was required to tip his hat to ladies he passed in the street, even if his hands were already full of parcels from Liberty’s.

Into this mess of filth and desperation stepped James Boyle. A man with a vision. A man with the drive to make life better. A man with a patent for a self-tipping hat.

It seems ridiculous now. It seemed a bit ridiculous then. James’s device sat underneath the hat and clamped to the head with four short metal legs. A nod of the head would activate the clockwork mechanism, which politely tipped the hat, and returning your head upright set it back into the starting position.

For SCIENCE!

For SCIENCE!

Ladies could be suitably greeted, and social etiquette restored, without ever needing to suffer the inconvenience of putting down your parcels or raising your hand.

You may mock, but you shouldn’t. James had every reason to think he was on to a good thing. His invention was based on the same premise as some of the most successful in history, from the wheel to the car to the computer.

The premise that people are lazy, and if you can make life easy for them, you’re on to a winner.

There’s very few absolutes in the world, especially in advertising. But this is one of them. Everyone, everywhere, wants an easier life.

If your ads can show that your product or your company makes life easier for your prospect, you’re going to sell more.

Lifehacker have built a huge following for their blog devoted to getting more done easier.

Tim Ferriss has made his name with his 4-Hour series of books. Work weeks, bodies, cooking… Tim will promise to help you master or achieve all of them in four hour stints. And what does that imply? That it’s going to be easy.

This is crucial. Tim’s first book was the 4 Hour Work Week, now something of a touchstone text for anyone wanting to quit the rat-race and make a living online. But unlike most bibles for internet living, Tim never once promised to make anyone rich. In fact, he promised the opposite – a business that would meet your daily needs and make a reasonably consistent five-figure-per-year income. Hardly Warren Buffet. But he promised you’d be able to achieve it easily, and that’s what attracted people.

So how do we make our products seem like they’ll be easy to use?

You might think that you should look at the advertising for one of the countless labour-saving devices for best practice here.

Instead, look at Lidl.

Lidl are developing a bit of a track record in on-topic, well-aimed advertising.

Just over a week ago, Sainsbury’s had one of those minor mess-ups that no-one ever cared about before Twitter existed, when someone put up a poster meant for staff motivation in a shop window.

Whoops.

Whoops.

Now, it should come as much of a shock that supermarkets are attempting to make you spend money. If it does, then I suggest you’re possibly not quite ready for this level of retail shopping.

But of course someone took a photo, and the photo got 5000 retweets, and Sainsbury’s were suitably embarrassed.

Within a couple of days, these posters began to appear in Lidl’s stores:

Translation: you just got pwned

Translation: you just got pwned

This is Britain, and everyone loves it when companies take snarky digs at each other. So naturally, this got a load of retweets too. Tons of free exposure for Lidl, and they never even mentioned Sainsbury’s in the ad.

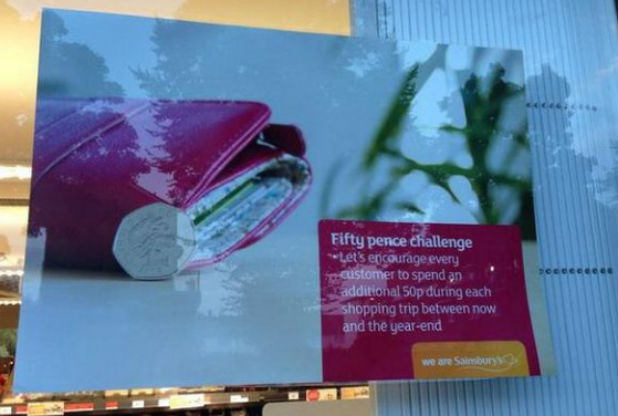

Now, they’re at it again.

Morrison’s recently launched a loyalty card in an attempt to claw back a bit of market share. The USP was that this loyalty card came with a price-match guarantee – if you could find the same product cheaper anywhere else, Morrison’s would give you points to make up the difference. And this wasn’t just matched against equivalent-tier supermarkets – Morrison’s also guarantee their prices against the budget supermarkets, Aldi and Lidl.

Lidl’s response:

All I wanted was some milk…

All I wanted was some milk…

This is how you demonstrate that you are the easier option. Put you and them in direct comparison. Remove all requirements for your prospect to think. Explain their process in mind-numbing detail and explain yours in a sentence or less. Make it obvious – completely black and white.

Of course, this is reversible. An equivalent reversed ad could be something like:

—–

Find 2 hours free for a shopping trip

Make a list of everything you need

Try to remember where you left your car keys

Hunt for your wallet

Get held up at the traffic lights

Be cut off by a bus driver

Park two blocks away because the car park is full

Discover you don’t have change to get a trolley

Spend ages hunting for every item on your list, because they’ve changed the layout again…

Try to work out if you’ll eat those 2-for-1 courgettes before they go bad

Carry everything the 2 blocks back to your car

Get stuck in a traffic jam on the way home

…or you could just do it all online at Morrisons.com, and be guaranteed the cheapest price for everything

—–

The principle is the same. The processes in both ads are the same. But this time, Morrison’s seems far better, because we’ve spread the Lidl process out over multiple lines, and the Morrison’s explanation begins ‘Or you could just…’

This is all it takes. Providing people with two options, and presenting yours in a way that makes it seem better. You don’t have to claim it’s the easiest solution on the market. You just have to show that it’s easier than whatever you’re comparing it to.

Emphasising ease alone isn’t necessarily going to make your product sell. James Boyle’s hat never got anywhere, possibly because fitting it into your favourite topper seemed like more work than just tipping your hat manually. But as Tim Ferriss, Lifehacker and Lidl will attest, it’ll get you a long way.

How can I convince JVs to mail my launch?

“If you want your launch to stand out, you’ve got to sell it.”

How can I persuade JVs to mail my launch?

Writing a good JV page helps.

No, after that. I can get JVs to sign up. I mean, more’d be great, but what I really want to know is how to get the ones who HAVE signed up to actually mail.

Oh, OK. Well, there’s a short answer and a long answer. The short answer is ‘better marketing’.

No, my marketing’s pretty good already. We’re launching an amazing product, the funnel’s tested and the copy pulls really well.

No, not better marketing during your launch. Better marketing ABOUT your launch.

I think maybe we’d better go for the long answer.

Sure. First off, you need to think about affiliates’ motivations when they sign up, whether they’ve grabbed a link or signed up to your JV list. Some affiliates are very discerning about what they sign up to and only do it when they’re pretty certain they do want to promote. Some affiliates are trigger-happy and sign up to stuff with an enthusiasm normally reserved for drunk solo-ad clicks. If you’re a more discerning affiliate, it can be a big mistake to think everyone works like you do.

OK – so you’re saying I haven’t got their commitment, I’ve just got their attention?

Exactly. And attention is good, but you need to build on it. You’ve got to convert it into interest, desire and action.

You make it sound like I’m trying to sell them something.

You are. You’re selling them your launch. You’re selling them the fact that your launch isn’t just something they can promote, it’s the BEST thing for them to promote. Just like you get your customers excited about your product with a prelaunch, you should be trying to get your affiliates excited too.

So how do I do that?

There’s a simple 3-step strategy for building excitement that works on everyone. 1: tell them they’re going to get something cool. 2: tell them when they’re going to get it. 3: keep telling them. It worked on you as a kid coming up to Christmas, and it’ll work on your affiliates coming up to your launch.

Can you give me a bit more detail on that?

Sure can, Virginia. You got your affiliates to sign up on your JV page by showing them all the cool stuff your launch was going to deliver: the amazing product, the hot commissions. So you’ve already done 1 and 2. Your job is #3. Keep in touch. Take every opportunity you can to remind them about why your launch is going to rock.

I’m already posting in the Skype and Facebook groups.

I’m sure you are, and so’s everyone else. But you’re probably posting up just general notices, right? Date, time, commission. Maybe something about how it’s going to be AWESOME!!1!

Well, yes. What’s wrong with that?

Nothing’s wrong with it. But those posts get attention, not engagement. You can build engagement through Skype and Facebook as well, but the most high-impact route will be to run a mailing campaign. That’s what your JV list is for. They’ve already shown interest either in this launch or one of your previous ones, and you can get in touch repeatedly.

I’m not sure. I can’t just keep e-mailing ‘look at my launch, it’s awesome’ every day. That’s just going to piss people off.

Actually, you can, and it won’t, as long as you’re smart about it.

Spill.

Look, there’s a lot going on with your launch. You know how exciting it is – you’re in the centre of it. Affiliates aren’t involved in the same way, so you’ve got to get them involved. Let them know when you hit every milestone, and every time, relate it back to why this milestone means they’re going to make a ton of cash. You got beta tester feedback? Show it to them, tell them about the new features you’ll be adding people have asked for. You’ve got your sales page back from the designer? Give them a link, and explain all the cool stuff your copywriter’s put in there that’s going to make your conversions insane. Every event is a new excuse to mail, and every excuse to mail lets you remind your affiliates why your launch is worth promoting. Every mail you send gets you more attention, and puts you at the front of your potential affiliates’ minds. And the more attention you’ve got, the more they’re thinking about you, the more likely they are to hit ‘send’.

OK. So how often should I mail?

As often as you like. This is just like any e-mail sequence – you’ve just got to stay interesting. As soon as you start to be boring, people will stop opening your mails. Realistically, every day might be a bit much – the more mails you send, the harder it is to find new, interesting things to say. But you can still mail a lot more often than you might think.

And this’ll make everyone who signs up on my JV page mail for me?

Everyone? No. There’s always people who’ll find an offer that better fits their list, or who are just too lazy or disorganised. More than you’d otherwise get? Absolutely.

It sounds kinda like a presell.

That’s because that’s what it is. If you want your launch to stand out, you’ve got to sell it, and marketing is marketing. You do this stuff all the time. It’s just a different audience.

The World’s Worst Actor (and why he’s better at content than you)

In 1810, the worst actor ever took the stage as Romeo.

His name was Robert Coates, and from a young age he’d known he was born to take the stage. The stage disagreed, but Coates was in possession of a £40,000 per year income. I’m not sure what that works out to today, but it’s definitely multiple millions, and the kind of cash that can open pretty much any door you like.

The most charitable way to describe Coates’ acting would be ‘unique’.

He came with his own costume. One theatre-goer described it as:

“His dress was outré in the extreme: whether Spanish, Italian, or English, no one could say; it was like nothing ever worn. In a cloak of sky-blue silk, profusely spangled, red pantaloons, a vest of white muslin, surmounted by an enormously thick cravat, and a wig à la Charles the Second, capped by an opera hat, he presented one of the most grotesque spectacles ever witnessed upon the stage.”

Despite knowing the whole of Romeo and Juliet off by heart, he delivered every line wrong. This was deliberate, because he felt he was improving the text.

If he liked a scene, he performed it multiple times. Deciding the ending of the original wasn’t quite right, he came on again to remove the lid of Juliet’s tomb with a crowbar. Occasionally he’d break off from a speech to beg some snuff from the audience.

The theatre manager, one William Wyatt Dimond, was by the end of the performance contemplating murder. After Coates’ eleventh death scene, he finally gave the order to drop the curtain.

The audience sat in silence.

And then broke into a standing ovation. They’d loved it.

These days, we’re used to more 4th-wall breaking performances. But this was Monty Python 160 years early. The content of this Romeo and Juliet certainly wasn’t what the audience had expected.

But in context, it fit perfectly. They’d come to the theatre to be entertained. And the worst actor in the world was VERY entertaining.

People underestimate the value of context, just like they underestimate the value of entertainment.

If you’re selling information, the best way to make people like it and want more isn’t to make the content of incredibly high quality, or reveal things they’d never known before. It’s to make sure that whatever you say, you’re entertaining while you say it.

That way, people will enjoy reading what you wrote.

In the context of them enjoying themselves, they’ll assume what you wrote is good. After all, they definitely think it’s good, and they wouldn’t think it was good if it wasn’t high-quality information, right?

This works in a very similar fashion to the authority effect – that we’re more likely to believe someone we perceive to have authority on a topic. And if we don’t have any actual data, the fact that they’re wearing a nice suit or up on stage will do. Put information in the context of authority, that information will gain authority by association.

Likewise, put a product in the context of something desireable, and the product becomes more desireable. (All those car ads with pretty women sat in the driving seat? I’m looking at you)

Or a more shareable example:

This doesn’t mean you can exist solely on style forever. Robert Coates’ theatre career was short – he was a one-joke act, and it didn’t take audiences long to not find that joke funny any more.

But when you’re trying to build a following or just make sure your readers keep coming back, what you say is rarely as important as how you say it.

What makes a good benefit?

What makes a good benefit?

Free wine with dinner always gets my vote.

Ha. Ha. I mean it. I know what my product’s features are, but how do I translate them into benefits? People keep telling me I need to.

Well, they’ve got a point.

But do they really? When I’m buying a product I’ll often just look at the feature list. I just need to know it does what I want it to do.

Yes, but you’re coming into the sale with a lot of knowledge. It’s all about context, and the problem hierarchy.

The problem hierarchy?

Yes. The more knowledge you have, the more specific a result you want, the closer features and benefits become. As an example, say you’re after a suit. If you know about tailoring, you’ll be able to look at a label, see that it’s made from Super 120s wool and know that’s what you’re after. If you don’t know about tailoring, you won’t know what Super 120s wool means. You need to be told that it strikes a good balance between durability and lightness.

So it’s about being able to make the connection?

Exactly. Features become benefits when your customer knows they want them. Regardless of how much knowledge you’ve got, you’re looking for the same result – a suit that’s comfortable to wear, but that you can still get a lot of use out of. But people have tunnel vision. They only see what they’re looking for. So your knowledgeable customer is specifically looking for Super 120s wool, and that’ll hook them in your advert. Your less knowledgeable customer may know, in theory, that certain grades of wool are better so they could work it out, but what they’ll be looking for is an explicit assurance that their suit will be comfortable and durable.

But if they can work it out, why do we need to state it?

Because then you’re making the customer do more work. People don’t like that kind of thing. You’ll basically never go wrong assuming your customers are incapable of independent thought.

OK. That actually sounds pretty simple.

In principle it’s not hard. A neat trick is to make sure you use the word ‘so’. Your product has FEATURE so BENEFIT. The word itself isn’t important, but it forces you to think about why the customer will care. Although – fair warning – there’s something else you need to consider too.

Of course there is. God forbid this stuff should ever be easy.

There are reasons why copywriters get paid a lot of money. Anyhow, understanding that the benefit is what the customer wants is the easy part. The trickier part is understanding exactly what the customer wants. Even most customers don’t know that.

Customers don’t know what they want?

Not often. Most people don’t. What they think they want is informed by how they’d like to be; what they actually want is determined by who they are.

That sounds like psychobabble.

Fair point. The thing is there’s certain desires people have that they feel guilty about having, handily summed up by the seven deadly sins. Which does make some sense – if people didn’t want them, they wouldn’t need to be sins, and we’ve been brought up thinking of them as sins so we don’t like to admit to wanting them.

Do you have an example?

Why yes, Virginia. Let’s go back to the suit, and think about pride. You might look at a suit and think you’d look great in it, but the price tag says £500. You know you can’t really justify spending that amount just because you could feel proud about how you’d look. You’ve likely got plenty of other clothes that make you look good already. So instead, you think up all the other reasons you ‘want’ it for. You’ve got an interview coming up. The material’s good quality. It’ll last a long time. It’s discounted. A good copywriter writing an advert for that suit will SHOW you that you’ll look amazing wearing it, and TELL you about all these other ‘benefits’. You let yourself be swayed by them, because then you feel like you’re buying it for valid reasons, not just pride. The benefit you REALLY want sells. The benefits you think you want justify.

That’s… that’s fucking insane. People are broken.

Welcome to the human race. It’s quite fun once you get used to it.

How Dogecoin. Such Positioning. Many Clever.

Oh Dogecoin, how I love thee.

Not to the extent of actually owning any. I have no interest in bringing down the capitalist system, I don’t care about having anonymous transactions, if you want to speculate there’s a million penny stocks looking for love and if you’re after an actual investment then the FTSE still looks a ton better than the hyperactive kangaroo that is any given cryptocurrency’s value graph.

But they are interesting, and Dogecoin is the smartest of the lot.

A few weeks ago, they supported their own Nascar racer. The community noticed that Josh Wise was without a sponsor. They needed to raise $55,000 in dogecoins for him to race. And they did it, in less than a week.

They’ve chosen a livery. I’m a little disappointed it doesn’t have ‘Such engine! How rapid!’ on it.

It’s not even the first time they’ve done something like this. Earlier in the year, they raised $13,000 to send the Jamaican bobsled team to the Olympics.

This is good advertising, and unique in the niche, but it came from the Dogecoin community thinking it’d be an awesome thing to do rather than some grand plan to get the cryptocurrency more notice, so it’s not why Dogecoin is smart.

Dogecoin is smart because it’s the only cryptocurrency to have mastered market positioning.

Despite having little interest in cryptocurrencies, I’d heard of Dogecoin long before this, because people talk about it. There’s several cryptocurrency options – people are founding them in much the same way people founded shovel shops in the gold rush – but most of them die out fast. Bitcoin has traction – it came first. Litecoin… also exists. Dogecoin is gaining ground, fast. Not long ago, Bitcoin Magazine was speculating on whether or not Dogecoin would actually depose Bitcoin itself from the top spot.

Why did it take off? Because it used positioning. It’s designed to stand out from the crowd.

Most cryptocurrencies have a logo that looks a bit like the Bitcoin one. Dogecoin has a Shiba Inu. It has a language, taken from the original Doge Inner Monologue meme. Very currency! How digital!

Dogecoin was created by programmer Billy Markus, with the explicit intention of making a ‘fun’ cryptocurrency. One that didn’t take itself too seriously.

It was different. It took off. The fun nature let it appeal to people who before then didn’t care about cryptocurrencies or what they stood for. It gave them a reason to talk about it. It gave them an excuse to buy. Ironically, of course.

Whatever market you’re in, you need to stand out. You need to have something you stand for.

That’s your position. It dictates how people see your brand. What they associate with you, and what box they put you in. Your position lets then define how they see themselves through their choice to use you.

As an example, take two supermarkets: Waitrose and Lidl.

Waitrose has positioned itself as high price, high quality. It can get away with charging more for its food, because people go in there expecting to pay a bit more. They shop at Waitrose because they are discerning customers, they pay for quality. Sometimes, they just want to show they can AFFORD to pay for quality.

Lidl has positioned itself as a budget chain. No-one is going to complain that the food they buy in Lidl isn’t as good as the food they could buy in Waitrose. If they wanted Waitrose food, they’d go there. They go to Lidl because it’s cheap. They’re price-conscious. They save the pennies.

Both of these brands are growing and successful. They’ve each established a position, and customers who want what their brand stands for instantly know where to go.

And crucially, despite both being supermarkets, both filling the same basic need, you could build one next to the other and they wouldn’t be in competition. They’ve got different target markets.

So how do you stand out?

Choosing a position isn’t just something to go in your marketing strategy. When you know what your brand stands for, you’ve got to push this message in all your copy, in all your advertising. Nothing Dogecoin does is entirely serious. The community is built on being fun.

Nor should you choose your position lightly, because it won’t just define your customers, it’ll define you.

When your customers associate you with something, they won’t react well if you ever break that association.

Exhibit A: Colgate Kitchen Entrees.

Mmm, minty fresh

God only knows what the thinking here was. Your customer base associates the name ‘Colgate’ with toothpaste, and you now attempt to sell them ready meals.

Unsurprisingly, it bombed, no-one particularly wanting to eat a meal that tasted of toothpaste.

Colgate as a brand survived in their core market, though not every company that’s tried to break their position has been so lucky.

(For a more successful take on selling multiple products, have a look at global domination corp Unilever. Everything they manufacture comes out under a different brand name, allowing them to position each product separately).

This isn’t to say you can’t expand outside your existing product range – you just have to do it in a way your customers find consistent.

Rolex could quite happily expand beyond watches, but they can’t keep the same brand and sell budget products. The name ‘Rolex’ conjures up a very special kind of luxury, the kind enjoyed by rich men, the kind enjoyed James Bond. Other trappings of that kind of luxury would fit well under the Rolex brand, but whatever they sell, it has to be expensive.

Your business doesn’t NEED a defining position. But having one could be the difference between being Dogecoin – a fast growing major player, sponsoring Nascar racers and being discussed as the competitor that could even topple Bitcoin one day – and being one of the crowd, never talked about because there’s nothing to say. Your call.

Such marketing. How success. WOW.

How can I convince people to add JV bonuses to their mailings?

“If I want you to build me a house, the best way to make you do so is simply to prove it’ll be worth your time.”

How can I convince my JVs to add bonuses to their mailings?

Well, there’s quite a few ways. But the most obvious and, as it happens, most effective, is to give them a good reason to do so.

Isn’t the reason obvious? They add a bonus, they’re making a better offer, so they make more money. Duh.

OK, maybe we need to go back to first principles here. I’ve got a deal for you – you build me a house, and I’ll pay you £5.

…what?

You build me a house, I’ll pay you £5. You’ll need to get all the materials yourself, but I will make sure all the coins you get are really shiny.

How about no?

Why not?

Because it’d take me ages to build a house. And I’d need to spend a ton more money on the materials. That’s a dumb plan.

It’s not that dumb for me. I’d get a house. But look – you’re not going to build me a house because the costs of doing so outweigh the benefits, right? Well, that’s true of any action. When affiliates put together a bonus for your launch it takes effort, time and money. It’s expensive. It’s a risk. You’ve got to show them that the benefits outweigh all that.

OK, fine. So how do I do that?

You’ve got two main routes to go down. You can either reduce the amount of effort, or emphasise the benefits. For reducing effort, you can provide some bonuses of your own for your affiliates to use. Not everyone’s going to want to use them out-of-the-box, but they’ll at least provide a starting point and give them some ideas. For benefits, do you have any proof that bonuses are actually going to make people convert better? Everyone says they does, but there’s a big difference between something ‘everyone knows’ and actually seeing a big difference in results in hard numbers.

So that’s all stuff you’d do on the JV page?

Yes. Of course, it’s also worth following up with all your biggest affiliates personally. Bonuses are leveraged products – from any given bonus, someone who usually sells 25 units on a mailing won’t get anywhere near as much benefit as someone who sells 250. This means your bigger affiliates are far more likely to put effort into creating bigger, better bonuses. They’ll get far more return from the same investment. If you can get in touch and see if there’s any way for you to make their job easier, that’ll make them even more likely to want to go the extra mile.

That sounds like effort.

Yeah, things that make any decent amount of money have an irritating habit of not being something you can do just by headbutting your keyboard. There are ways you can incentivise them without getting directly involved, though.

Oh really?

Really. Your JV competition is the strongest. If the next prize level up comes with an extra $1000 in prize money – or if it’s currently occupied by someone they really, really want to beat – then that’s going to factor into any affiliate’s cost/benefit calculation. If the extra sales don’t make it worth it, the extra prize money might.

OK, that makes some sense. Is there anything I can do that isn’t going to cost me money, though?

So you know, we’re venturing dangerously into ‘moon on a stick’ territory here. But as it happens, yes. People like to be consistent in their actions, and you can use this as a powerful psychological trigger. It’s one of the few things like this you can describe as ‘weapons-grade’ and be completely accurate – the Chinese used it in the Korean War to turn American POWs into communists.

Tell me more…

I don’t want to go too much into the psychology here – go read Influence, if you’re interested – but the method works like this. In one of the JV rooms, shortly before your launch, post up a question like ‘should you give your list extra bonuses when you promote products?’. A load of people will say yes, and as soon as they’ve done that, they’ve made a public commitment. Having done that, their desire to be consistent will make them more likely to give bonuses on their next promotions – especially if you keep the conversation going by making further posts and using their comments as social proof that bonuses are awesome on your JV page.

And that really works?

Yes and no. Does it affect people, and does it make them a bit more likely to provide a bonus? Yes, absolutely, and they won’t even know it’s happening. Is it as strong as simply providing a compelling cost/benefit case for giving a bonus, either in person or on your JV page? Hell no. This kind of stuff might make you a bit easier to convince, but if I want you to build me a house, the best way to make you do so is simply to prove it’ll be worth your time.

Endowment, FTS, And The Art Of Getting More Mailings

This is about psychology, and a quick way of using it to get more mailings for your launches.

It’s a way of helping your top JVs feel invested and excited, and giving them something they want to fight for.

It’s also what caused the top executives of an entire industry to suffer a fit of collective insanity that cost them £17 billion.

This happened in the year 2000, when people still knew what Netscape was and the internet looked like this:

We didn’t even have 3G, and that’s why the madness started. The UK government was auctioning off the spectrum for the mobile phone companies to use on their networks.

This was one of the first 3G auctions, so it attracted a lot of interest. The bidding was conducted in several rounds – each company submitted a bid for each of the 5 potential licences, and at the end of the day it was made public knowledge who was winning and how much they’d bid.

The next day, everyone got to bid again.

And a funny thing happened.

You’d expect companies to make their bids associated with costs and benefits.

If you know you can make $1000 from an asset, you don’t offer to buy it for $1500.

And initially, that’s what happened. BT estimated the value of their chunk of 3G spectrum to be £300 million.

Their final bid was £4 billion.

Vodafone paid almost £6 billion for their licence.

The telecoms industry collectively spent £22.5 billion on the UK 3G licences. That’s £17 billion more than they could reasonably expect to make back.

What happened is called the Endowment Effect.

We value something more when we own it.

Daniel Kahneman ran a study in which half the group were given coffee mugs. They were then given the chance to sell these mugs to the other half of the group, if they could agree a price.

Very few mugs were sold. A poll afterward revealed that most students wouldn’t sell their mugs for less than $5.25, but most wouldn’t buy for more than $2.25.

You can see the same effect in the housing market, with people convinced their home is worth an unrealistic amount.

The curious thing is that this even works when we almost own something. Those telecoms executives saw that one day, they were on top of the bidding. The licence was ‘theirs’.

The next day, someone had bid higher. It had been taken away from them.

And anyone with faith in these incredibly well-paid, smart executives would like to think they’d go back to considering their costs and benefits and make a sensible decision for their company.

Their actual thought process followed the FTS Principle – something you’re no doubt familiar with when someone tries to take away something you consider yours.

It was, in its entirety:

Fuck. That. Shit.

And this brings us back to JVs.

A lot of people will run big JV competitions, thinking that massive prizes will attract loads of affiliates.

They won’t.

They’ll attract a couple, but the only people who care about your $10,000 top prize are the ones with a vampire’s chance in the Sahara of winning it, and there’s a good chance you know them well enough that they’d promote anyway. Your competition is a tie-breaker, not a honey-trap.

But where competitions come into their own is through the endowment effect.

It kicks in as soon as you send out that first leaderboard mailing.

Maybe your affiliates weren’t that bothered about your $200 5th-place prize when they signed up to promote.

But when they find they’re in line to win it, it becomes a LOT more important.

Often, it’ll be important enough to justify a second, third and fourth mailing – especially if the guy they might lose it to is a mate. Losing something is hard. Losing something to someone who’s going to rub it in your face next time you have a Skype chat… well, let me refer you back to the FTS Principle above.

Of course the amount of money does matter – bigger amounts are worth more. But the driver is this fear of loss. That’s why, on your JV leaderboard, you should make sure everyone knows just how precarious their position is, and make a big thing of it when the rankings change.

In something like a launch, there’s nothing as exciting as fighting to keep hold of what’s yours.

And the best part is that no-one’s a loser. In the 3G auction, the telecoms companies massively overpaid for the assets. Their share prices tumbled.

But during a launch, no-one’s losing money. Everyone’s making it.

This is just one of the tools you’ve got to make sure everyone makes more.

Webinar: Turning Bitcoins Into Gold – Adding Value Without Adding Content

A few days ago, I delivered a talk at the UK Marketing Summit 2014, organised by Simon Warner, Michelle O’Callaghan and Richard Fairbairn.

As it was the first time I’d ever given this talk, I was a bit worried about the reaction. It turned out better than I’d ever expected:

So in a couple of days, I’m running a webinar of the same talk for everyone who couldn’t make it.

The talk is all about value, and how you can add value to your products without changing them.

On the way, we’ll talk about bitcoins and breakfast cereal and paintings and toasters.

And at the end of it, you’ll know how to charge more for what you currently sell and still keep the same conversions.

The webinar is happening on Monday 24th March 2014, at 3PM GMT. There are 100 spots available, so if you want to come along (or even if you just want to get the replay link), sign up here:

FAQ:

Will it be fun?

Yes it will. Despite this being the first time I’d given the talk and of course forgetting a load of the material, it got a really good reaction.

Also, people found the bit about breakfast cereal really funny.

I like bitcoins and breakfast cereal and paintings and toasters. Will they be included?

Why yes! It’s as if you read my mind!

What are you pitching?

I’m not. This is me practicing how to talk to people without being terrified the sky will fall on my head.

Is the sky likely to fall on your head?

No. This knowledge makes the irrational fear even more irritating.

I dunno, I don’t really have time for a 2-hour webinar…

Me neither. The talk will last about 30 minutes, and then there’ll be a bit of time for questions.

Will there be a replay?

Barring technical fuck-ups, yes. Anyone on the list will be sent the link.

Where do I sign up?

Right here:

Of cons, commandments and capturing customers

In 1925, a man walked into the Hotel de Crillon, one of the most prestigious hotels in Paris. Five other men entered with him, but this man was the one who was special.

This man would buy the Eiffel Tower.

His name was Andre Poisson. He’d been invited to the Hotel de Crillon by the deputy-director of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs, as a leading scrap metal merchant known for his honesty and discretion.

After a short presentation, all six men were taken by limousine to inspect the Eiffel Tower. At this time, it was a bit of a wreck. It hadn’t been maintained well and the costs of keeping it painted were prohibitive.

The Minister told the group that due to an expected public outcry, they must keep all details secret until the deal was done. He then invited bids, to be submitted no later than tomorrow.

Andre Poisson jumped at the chance. He’d never felt like he was in the ‘inner circle’ of Paris business – landing this deal would put him into the big leagues.

His wife was a bit more suspicious. Why all the discretion?

The Minister set up another meeting to explain himself. As a government minister, his salary did not cover the kind of lifestyle he enjoyed. That meant he had to find ways to supplement it, and as such his dealings required some amount of discretion.

Selling the Eiffel Tower was unusual. Corrupt government officials were not. Satisfied, Andre handed over the money for the Eiffel Tower and a large bribe.

Of course, Andre hadn’t really bought the Eiffel Tower. He’d just given a large amount of money to one of the world’s best con-men, Victor Lustig.

It’s easy to laugh at Andre, but that’s under-estimating just how good Victor Lustig was at what he did.

The con he set up was well-presented. The presentation was in a prestigious location, and the limousine was expensive.

He played upon Andre’s insecurities, that feeling of wanting to take his business to the next level. Which of us hasn’t wanted that?

He made the unfamiliar, familiar. He made the unusual nature of the deal seem usual by clothing it in something – government corruption – that Andre dealt with every day.

Also, the deal really wasn’t that far-fetched. These days, the Eiffel Tower is a multi-billion dollar tourist attraction. In 1925, it was a poorly-maintained wreck. It was never even meant to be a permanent structure – it was built for the 1889 Paris Exposition, originally planned to be taken down in 1909.

(Remember that, next time you’re taking that lift all the way to the top)

But what Victor was incredibly good at was gaining trust.

And this is where we can learn something from him.

When you have someone’s trust, you can sell them pretty much anything.

Victor summed up his talents into ‘Ten Commandments for Con Men’.

- Be a patient listener (it is this, not fast talking, that gets a con man his coups).

- Never look bored.

- Wait for the other person to reveal any political opinions, then agree with them.

- Let the other person reveal religious views, then have the same ones.

- Hint at sex talk, but don’t follow it up unless the other person shows a strong interest.

- Never discuss illness, unless some special concern is shown.

- Never pry into a person’s personal circumstances (they’ll tell you all eventually).

- Never boast – just let your importance be quietly obvious.

- Never be untidy.

- Never get drunk.

And you can turn these into principles that will help you sell anything to anyone:

Care about your customer (1, 2, 5)

Think like your customer (3, 4)

Make your customer feel good (6, 7, 8)

Respect your customer (9, 10)

‘Sex talk’ is probably best not pursued, even if it does show you care about your customer. There’s no denying, though, that if you’re faced with a choice between two coffee shops, you’re going to go for the one where you fancy the waitress.

Ultimately, Victor was self-defeating. If he’d used his amazing skills at gaining trust to make that crucial first sale, then delivered awesome products so they kept coming back, he could have died a millionaire.

As it was, he died penniless, of pneumonia, in Alcatraz.

But this doesn’t mean you can’t use these exact same skills to provide something of real value to the world.

Because if they can successfully sell the Eiffel Tower, just imagine what they can do for you.

When long copy doesn’t work

Ask any experienced marketer, and they’ll tell you ‘long copy outpulls short every time’.

And usually, it does.

But there’s a weird double-standard at the moment where the same people who will encourage you to make your copy as long as possible insist that your VSLs should be at most 4 minutes long, because ‘people don’t watch long videos’.

And sometimes, ‘long’ copy can be remarkably short. The ’2 Young Men’ Wall Street Journal sales letter, sent to colder traffic than you’ll ever find online, generated approximately a billion dollars, and did it all with 800 words.

So which is it?

You’ve probably heard the Gary Halbert quote: “A sales letter can’t be too long, only too boring.”

This is true.

But.

But but but.

The single easiest way of making copy boring is making it too damn long.

I’ve got to admit, my heart sinks a bit every time I’m given a 5,500 word sales letter to review for a product that only costs $17.

Because it’s possible that you really do need all those words. Maybe your product is so complicated or your prospects so cold that you really need the equivalent of 3 chapters of a novel to convince someone that it’s worth $17.

But you probably don’t.

Length does not equal quality. When you’ve said enough to convince your prospect, stop.

So short copy is best?

Well, no. Long copy tends to outpull short for a reason.

When I write a sales letter, I’m not expecting all 3000 words to be needed to convince any given propsect. I’m expecting maybe 500 at most to be important.

But it’s a different 500 for everyone.

Short copy fails when the reason it’s short is that the writer has left out a load of selling points. It simply can’t convince as many people.

Long copy succeeds when it can carry people through the parts they’re not interested in without them noticing.

And the best way to do that is to use as few words as possible to say them.

(The same is true for VSLs, by the way. Avengers Assemble was 2 and a half hours long and $1 billion worth of people sat through it in the first 3 weeks. If people stop watching your VSL after 4 minutes, it’s not because they’re genetically programmed to stop. It’s because your VSL was fucking boring)

Here’s the tl;dr version:

- Make it as long as it needs to be. Don’t leave anything out that could sway your prospect.

- Make it as short as possible. Trim as many words as you can without losing your selling points.

- You live and die by how interesting you are to your prospect. You don’t need to have them gripped with every sentence, but leave it too long to get their interest back and they’ll drop you faster than a blackhatter over a cliff.

Don’t worry if you find that hard. I’ve been writing professionally for years, and believe me, this stuff isn’t easy.

But don’t obsess over your word count. There’s no magic number, there’s no size-line your copy has to cross to be a massive converter.

Instead, do what Gary Halbert did and take the advice of the King of Hearts:

“Start at the beginning. Continue until you reach the end. Then stop.”